Americans overwhelmingly rely on their own wheels to get around. Of the 130 million households across the country, 92% have at least one automobile, van, truck, or other vehicle, and 37% own two or more.

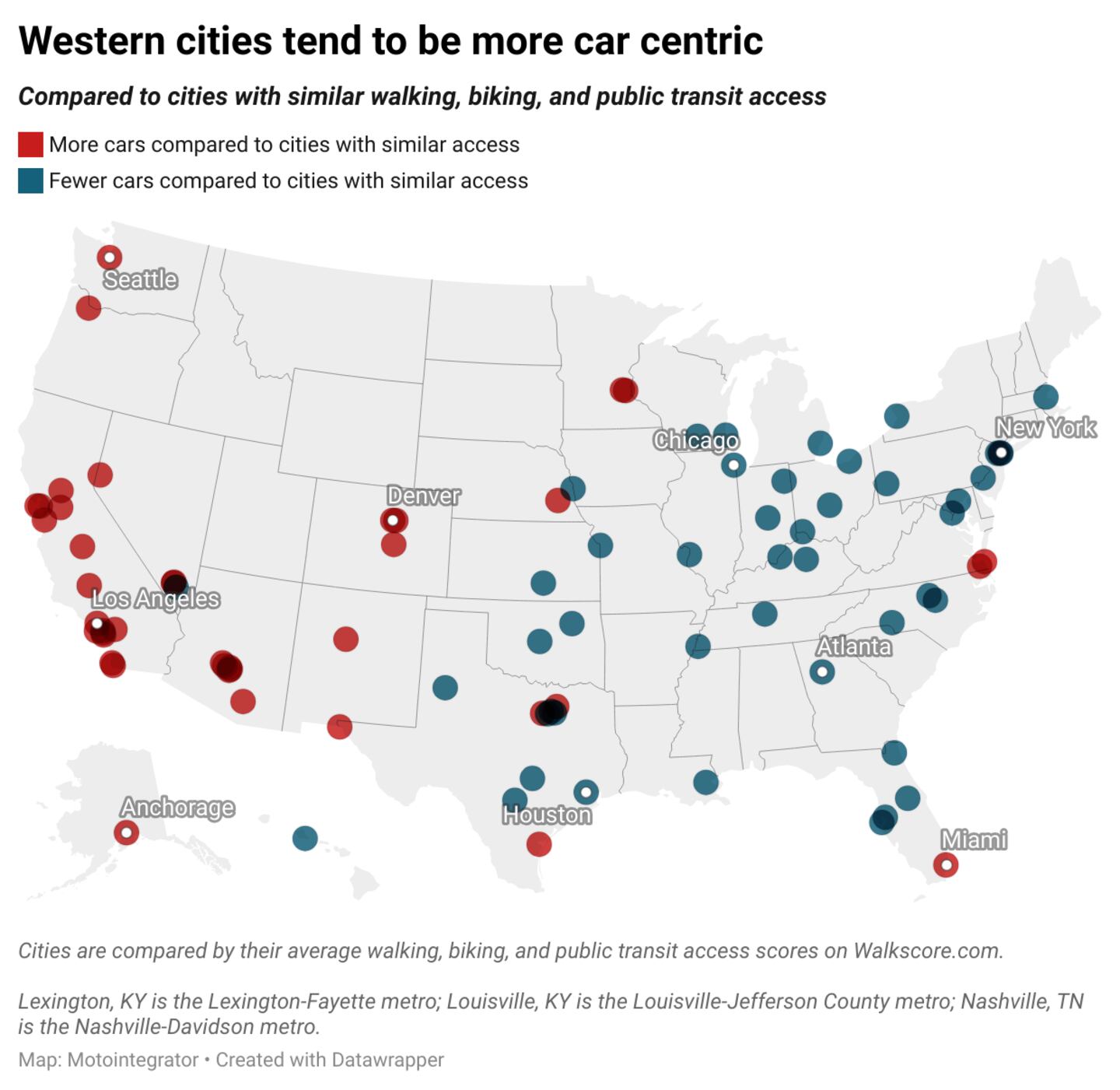

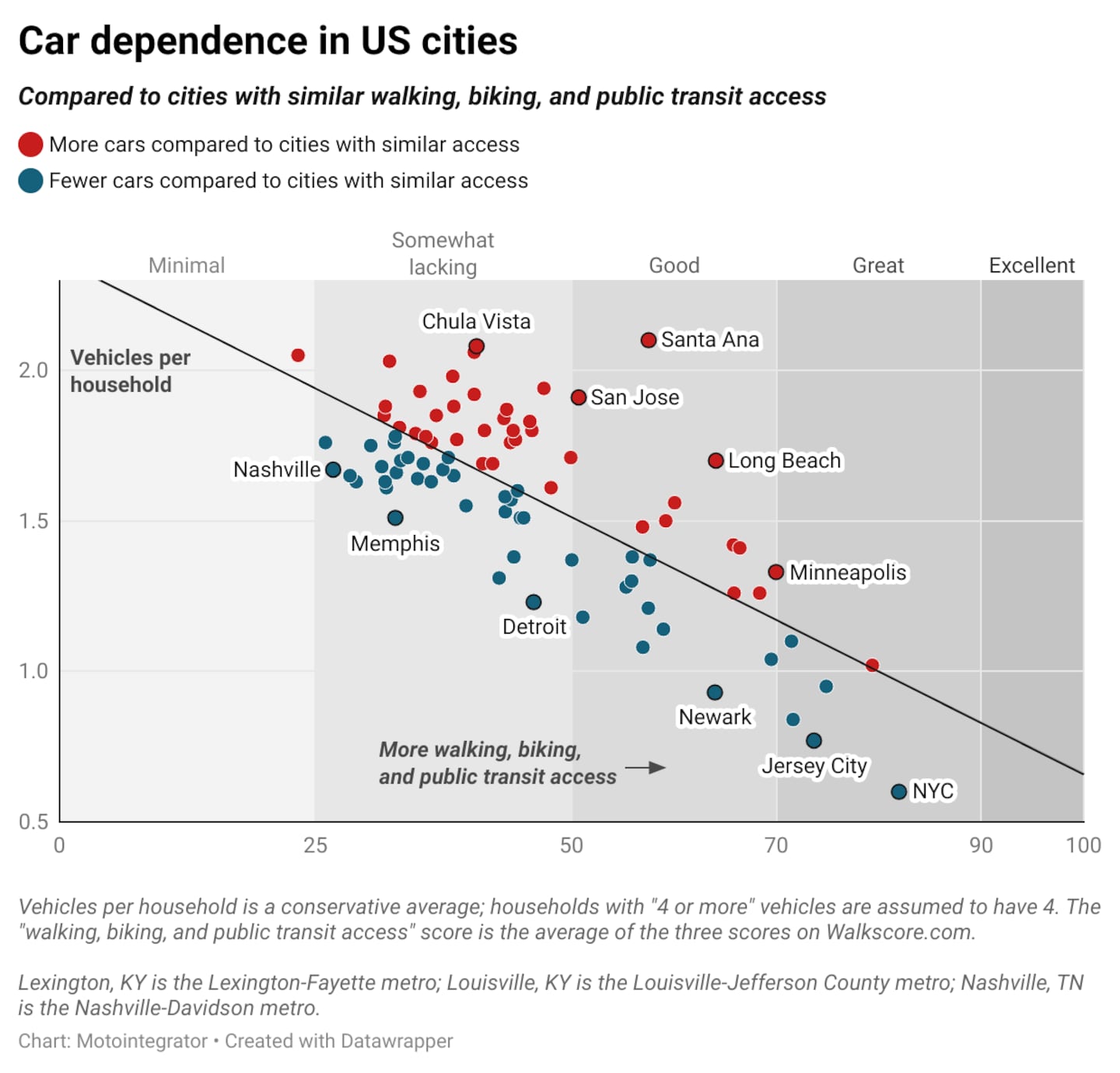

While it may feel like every urban area is catastrophically congested with vehicles, some cities are more car-centric than others, either out of necessity or due to a penchant for that luxury. A new analysis finds that there is a great range in car dependence in U.S. cities—even between cities with similar access to alternative transit options.

The analysis, conducted by Motointegrator, a car-parts retailer, and the research experts at DataPulse Research, shows that Western cities are particularly entrenched in car culture, even though many of them—especially those in California—offer walkable neighborhoods, bike-friendly infrastructure, and decent public transit options.

To find the worst offenders, the team looked at all cities with more than 250,000 people, calculated the average number of cars per household, and then compared cities with similar mobility characteristics like walkability and public transit.

Motointegrator

Car Culture in Santa Ana vs. Walkable Cities

Why are mobility characteristics important? Take, for example, the cities of Santa Ana, CA, where the average household owns more than two cars, versus Jersey City, NJ, where the average is less than one vehicle per household. Jersey City is considered much more walkable and has a more robust transit system than Santa Ana, according to Walkscore.com. That context is important.

In order to find out whether Santa Ana has an excessive and needless car culture, or one that is expected and justified, DataPulse compared the city to other U.S. cities with similar walking, biking, and transit access.

Motointegrator

California Sits on Top

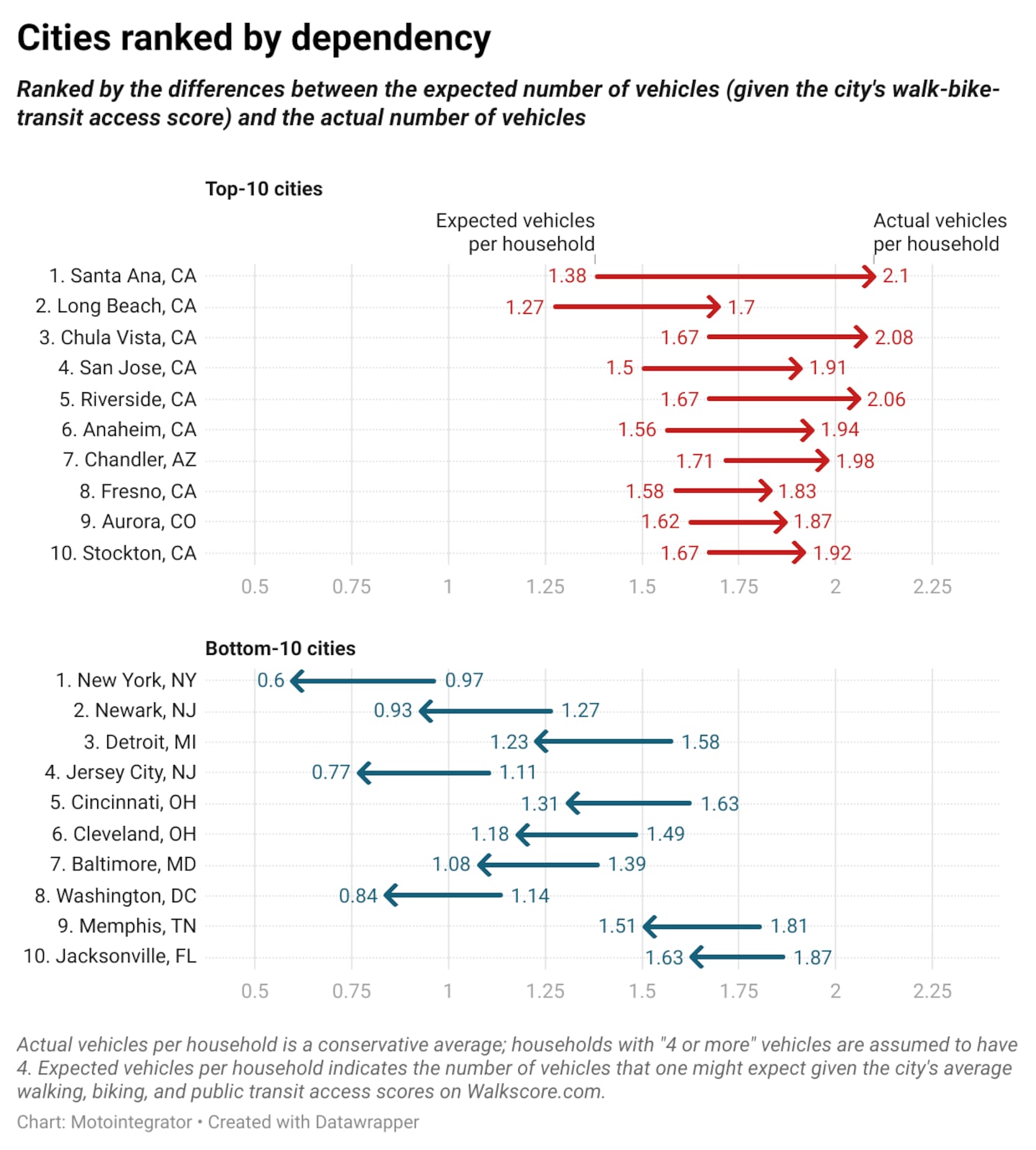

Santa Ana was stacked up against cities like Pittsburgh, PA, and Baltimore, MD, which have similar average walking, biking, and transit scores. And, as it turns out, Santa Ana is still far more car-centric than its East Coast counterparts. The city has 2.1 cars per household compared to 1.2 and 1.1 vehicles for Pittsburgh and Baltimore, respectively.

The researchers used this method to determine the "expected" number of vehicles per household based on each city's average walking, transit, and biking scores. Cities that showed higher than expected vehicle counts were deemed excessively dependent on their cars.

Of the top 10 cities with the highest dependency, eight are in California. Santa Ana takes the top spot, as it has 0.71 more vehicles per household than one might expect for a city with its transit and walking scores. Next is Long Beach, CA, which has 0.43 more vehicles than one would expect, followed closely by Chula Vista, CA, with 0.41 more vehicles than expected.

At the other end of the spectrum are cities with fewer private vehicles than expected. Among them, New York City takes the top spot. The Big Apple has only 0.6 vehicles per household (or about one for every other household), even though its walking and transit score suggests it should be closer to one vehicle per household.

Motointegrator

When Is Car Dependency Justified?

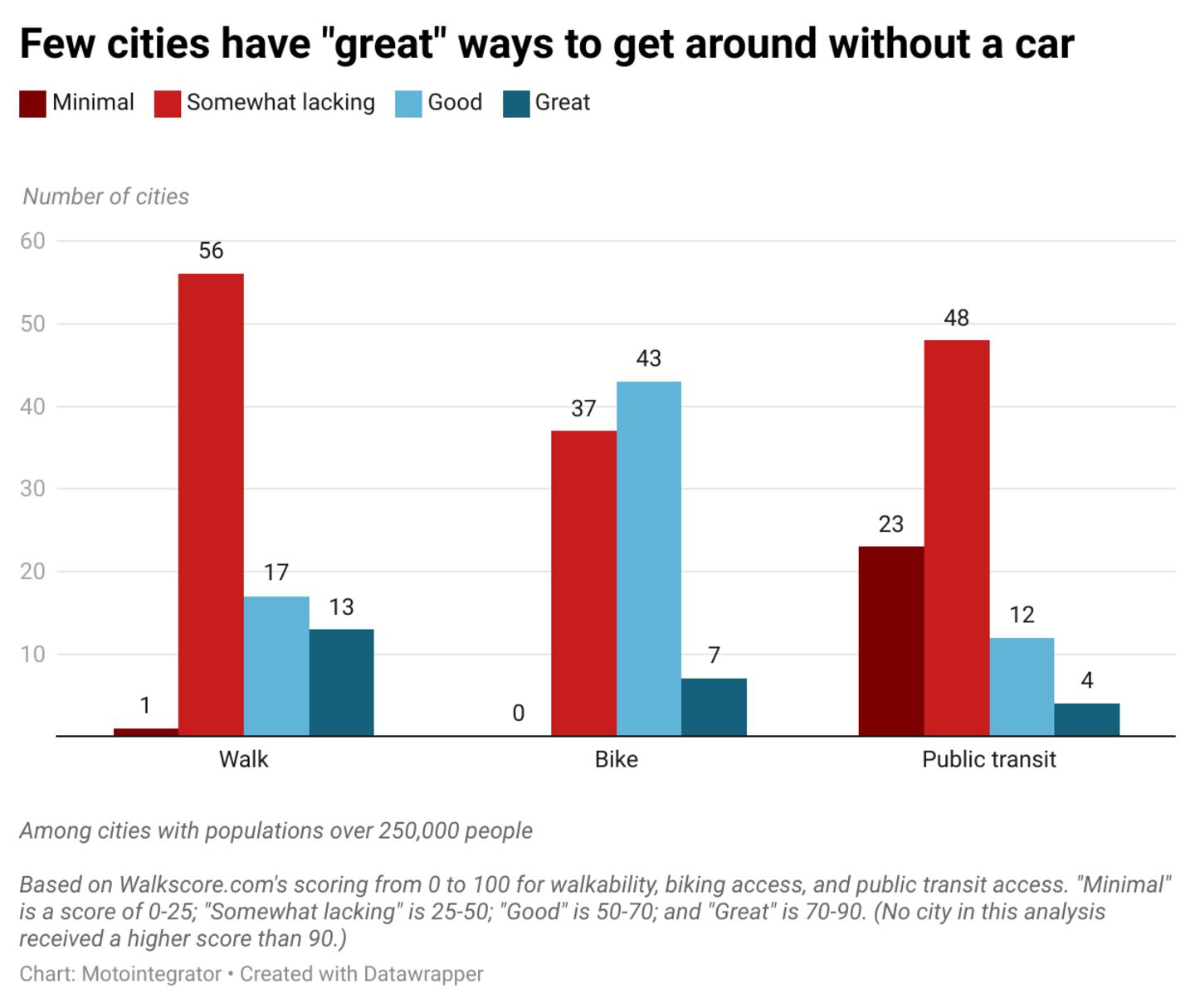

People who live in cities may not feel a great need for personal vehicles—so long as they can get around in other ways. However, many American cities are not walkable, nor do they offer viable alternatives such as robust public transit or biking infrastructure.

Of the 87 cities in the study, only a handful get high scores for walking, biking, and public transit on Walkscore.com. On a scale of 0 to 100, most of them fall in the 25 to 50 range, which indicates that the accessibility or infrastructure for alternative mobility is "somewhat lacking." Only a handful have "great" scores of 70 to 90. None of the cities achieve "excellent" scores above 90.

Perhaps this explains why so many U.S. urban households own one, two, or even three vehicles.

As the chart below shows, cities with lower average Walkscore scores (on the left) tend to have more vehicles per household, while cities with higher scores (on the right) generally have fewer vehicles. The bulk of the cities fall to the left of the chart, clustered between 25 and 50, indicating the "somewhat lacking" range.

City residents who lack alternative options may feel their car reliance is justified. However, they might not realize that people in other cities with similar mobility access are managing with fewer cars. By comparing cities according to mobility characteristics, it becomes evident that many cities (marked by red dots) have unnecessary or excessive car reliance compared to their counterparts (marked by blue dots).

Motointegrator

Why It Matters

As the U.S. looks to a greener future, cities need to better understand whether car dependence grows out of need or desire. This study challenges the assumption that all car ownership is strictly a necessity. It turns out that many cities with relatively robust infrastructure for walking, biking, and public transit can exhibit excessive reliance on cars, while others with limited options manage to get by with fewer vehicles. The greatest offenders tend to be in the Western half of the country.

It is clearly possible for urban areas to function with fewer cars. The question is whether cities are willing to follow the example set by others across the state—or across the country.

Methodology

This study looks at which cities in the U.S. have the most car access relative to the alternative mobility options available. The research team focused on the largest cities in the U.S.—those with at least 250,000 people (a total of 91 cities).

The team calculated the average number of vehicles per household in each city. The data for this calculation comes from the American Community Survey's 2023 estimates of "vehicles available" by household (Table B08201, available via the Census Bureau). This is a conservative average, as any households with "four or more" vehicles are assumed to have four.

Data for non-car mobility comes from Walkscore.com, a site owned by the real estate brokerage Redfin that scores neighborhoods and cities by a) walkability, b) bike riding access, and c) public transportation options. Each of these three metrics is ranked from 0 to 100, where the higher the score, the easier it is to get around. To get an overall sense of what non-car mobility looks like in each city, the team averaged the three metrics. (Greensboro, NC, Winston-Salem, NC, Toledo, OH, and Laredo, TX are not included, as they do not have public transit scores on Walkscore.com.)

Using the average cars per household and the average walk-bike-transit score, DataPulse ran a regression analysis to determine the expected number of vehicles per household for each score. The team then compared the actual number of vehicles per household to the expected number. This revealed whether each city had relatively more cars or relatively fewer cars compared to cities with similar walk-bike-transit scores.

This story originally appeared on Motointegrator, was produced in collaboration with DataPulse and distributed by Stacker.